Co-written by Charlotte Hochman and Kristian Simsarian

Reading Time: 9 minutes

As teachers of technology-shaping skills such as interaction design and engineering, we have witnessed not only the growing power of technology but the increasing importance of helping students see the bigger systems when shaping these technologies. We see the need to enable a new generation of technical experts who are fluent in understanding, interpreting, and improving human systems, not just technical ones. Here we share four teaching practices that educators can use to increase this critical yet under-delivered capacity.

As we write, the world is in a chaotic pandemic with increasing social polarities that are often fueled by technology. While the core educational focus of most technical curricula is to increase the capacity for inventive technical solutions, we see a need for these solutions to also increase social interconnectedness and resilience. To do this we believe future solution providers need to practice understanding and intervening in complex social systems while still in school.

Software is eating the world

Observing the increasing social impact of technology leads us to a key question:

How can we help these technical minds have a working knowledge of complex systems, including human systems, that complement their technical competence?

Here are a few reasons why this is a pressing question:

- With the Fourth Industrial Revolution, low-level technical tasks will be automated. The focus of our learning needs to shift to excel at quintessentially human tasks, such as being creative and dealing with complex, unexpected human behaviour.

- The technical systems we are creating are often disconnected from the wider systems they must exist within. The example of the algorithmic bias is a telling one. We all need to be aware of complex, diverse, messy systems, such as human systems, especially if we are building technical ones.

- Today four out of five of the largest companies in the world are technology-based, and their products are integrated into our daily lives. With the 2016 misuse of social media in the UK and US elections, it is clear that software plays a key role in defining global events. Shaping technology is shaping significant parts of global events.

- In 2011, influential venture capitalist Marc Andreeson wrote an essay Software is eating the world that anticipated how information technology platforms would soon drive all of the business and, as a result, culture. To shape technology is to shape global culture.

In essence, we are witness to a world where our students graduate into helping scale new organizations, in new industries, that impact billions of users with unintended consequences and social externalities that they are not currently equipped to design for.

Students are rarely taught tools that help them understand, let alone forecast, the social-cultural implications of their work. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, which self-defines as “the world’s largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity”, has only just included ethics as part of its curriculum.

Given the gaps in the larger social systems view from technical students, how will our students navigate this and not be a part of the problem?

Our belief is that part of the answer lies in giving students exposure and practice in relation to social systems during their technical studies.

We believe there are four crucial steps in helping students acquire an understanding of human systems: giving students a new language, making systems visible, inspiring students with whole systems thinkers, and giving them an opportunity to practice in the field.

1. Give students a new language

Words count. They give us the ability to not just name something, but to build, manipulate and design around a complex concept. The dominant vocabulary in the business world does not relate to systems: it is reductive. Often technical vocabulary is reductive too, at least with respect to the social arena. We believe it is important to give students words to name phenomena that the business or technical culture do not value, so they can apply systems-thinking in contexts where no such perspective is present.

This is some of the language relating to human systems which we recommend as the basic kit for students:

Externalities: essential for students to be able to pin down when a company, for instance, is not thinking about its consequences on the broader system – whether these consequences be positive or negative.

Theories of change show activities in their context: what it took to create them, and what they produce in their turn, what it will take to shift them. They express how different elements in a system can be articulated toward positive outcomes.

Regenerative mindset, or regenerative design: a shift in the conversation from “doing less bad” to creating systems (places, companies and communities) that have the capacity to evolve towards more health and vitality over time.

Leverage points: in Donella Meadow’s words, “places within a complex system (a corporation, an economy, a living body, a city, an ecosystem) where a small shift in one thing can produce big changes in everything.” Good design is deliberate about delivering a leverage point response.

2. Make the wider systems visible

When a project starts, by definition the designer’s focus narrows. So it’s essential to learn to pause to reflect on the larger system, and have tools to monitor the intervention from a systems perspective.

A tool to understand leverage points and be able to identify them within a system to inform the choice of intervention is the iceberg model. This tool pushes students to look beyond events happening, to patterns of behaviour, systems infrastructure and mental models. In the iceberg, each element may be the “context” or precondition for the next.

We have tried it out as an embodied exercise for students, in the form of what Kristian calls a “system sculpture.” Each student physically represents an element of the system in the room. The system becomes gradually visible as students identify, name, and embody different elements that compose the system and manifest it physically in the room.

3. Get students inspired by whole-system thinkers

Eliel Saarinen

Externalities also become visible in a greater context or greater timespan. Having students reflectively and reflexively practice zooming in and out of time and context is a powerful habit to aid in visualizing the bigger system.

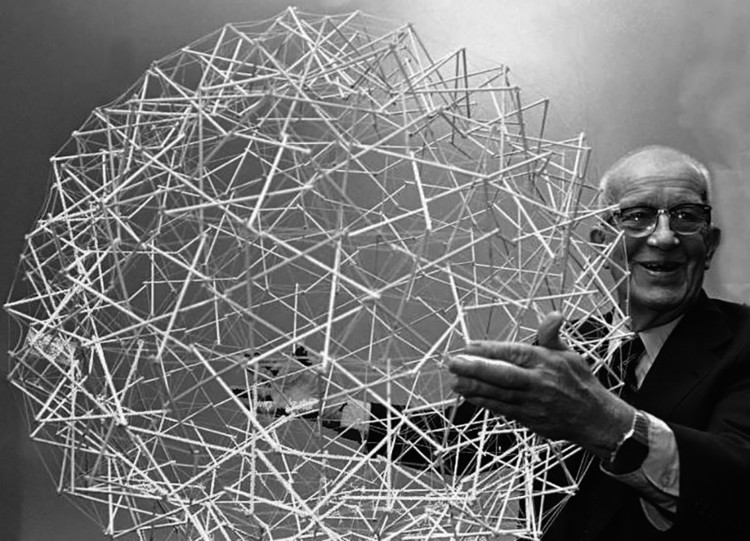

“Start with the cosmos”, recommends Buckminster Fuller, iconic whole-systems thinker, and inventor. From where he stands, the only relevant initial starting point for context is the cosmos. From there, we must zoom in on whatever seems relevant in the system, to create relationships to the subject of the inquiry at hand. That way we don’t miss the externalities of a system in our design.

Another visionary mind that students might enjoy discovering is that of architect Eliel Saarinen. “Always design a thing by considering it in its next larger context”, he writes. “ – a chair in a room, a room in a house, a house in an environment, an environment in a city plan”. This has become a mantra to many of our design students and is applicable in different sectors. There is always a “next larger context” to any intervention. Can students learn to read that next larger context before they intervene?

Getting familiar with whole-systems thinkers and doers is an eye-opener for many students who have spent years going deep on technical skills and looking at systems that are not human-centric.

4. Practice in the field

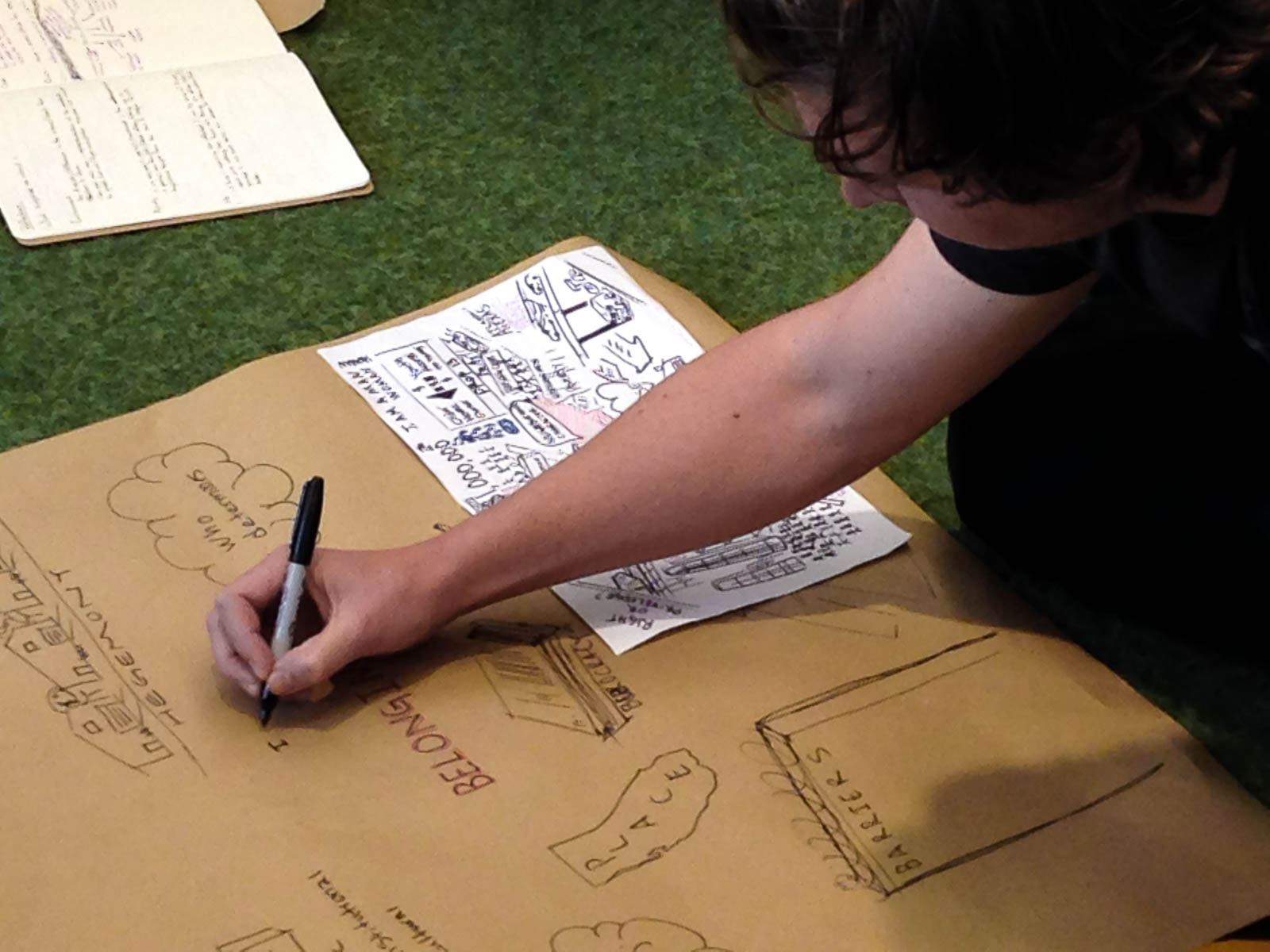

To experiment with complex system interventions, as for anything else, there’s nothing as effective as actual practice.

Higher education provides the perfect setting for trying out what will of course be a messy experience, in a de-risked situation.

Service education can be a useful format to let students try for themselves. It consists of students taking part in projects in the “real world” outside of the place of learning, often in partnership with community-based organizations.

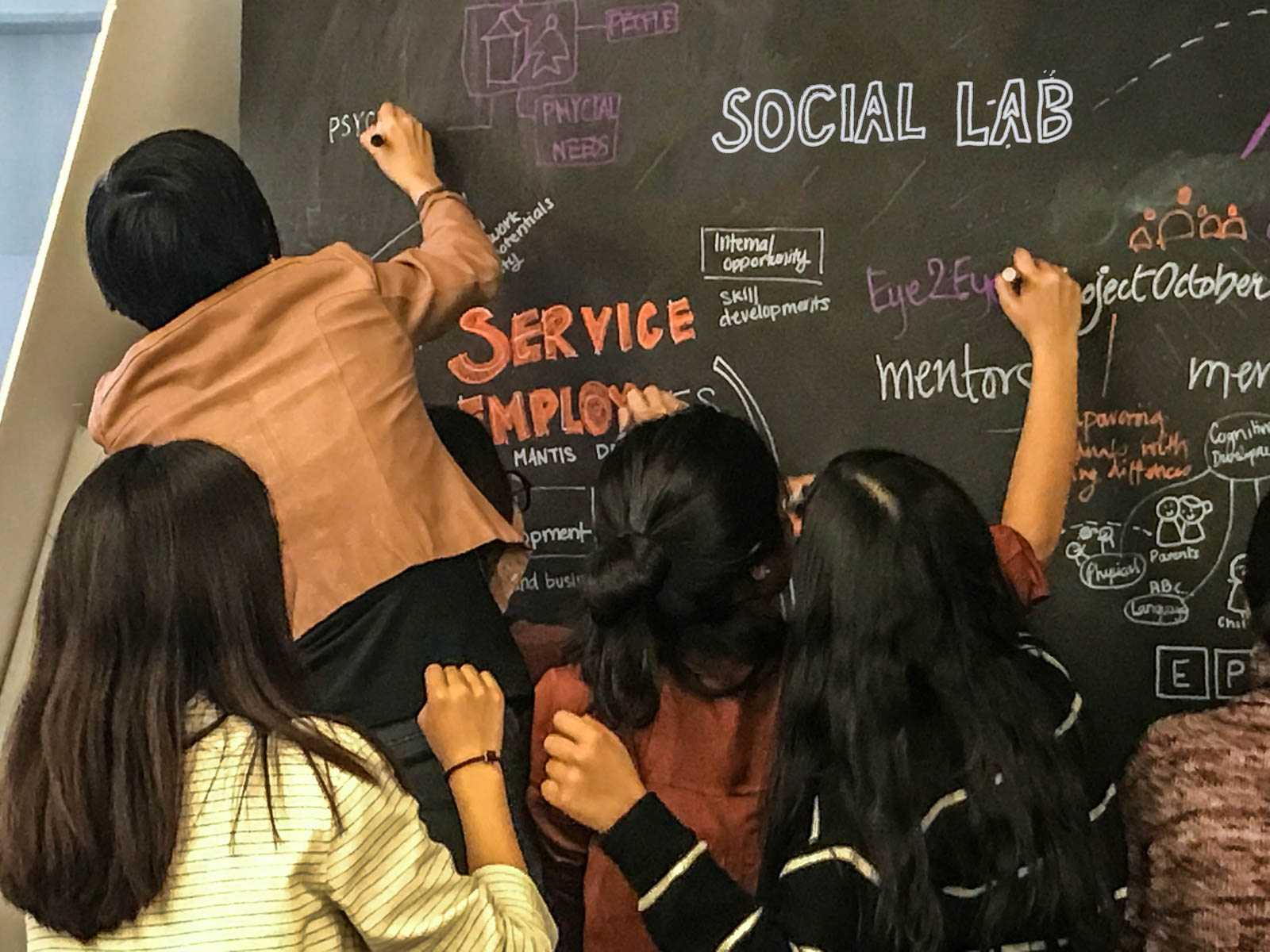

The Social Change Lab at the California College of the Arts is an example of service-based learning we have both led. Masters-level Interaction Design students go into the San Francisco and Bay Area community to work on pressing challenges. Their work mainly happens in the field with their partners supplemented by complementary side-coaching and instruction in the classroom studio. In this way students practice (re-)adapting their interventions with whatever live data the people and “social system” is providing them through their experience.

Our students’ interventions focus on complex social challenges (a.k.a wicked problems) present in the communities around campus, on topics as diverse as access to healthcare, education inequality, loneliness, or racial divides.

Although more work, we have found it best to facilitate the set-up of the collaboration between the students and the community partner, to avoid students taking commitments within the community that they would not be able to deliver on and set expectations with the partners.

The above steps 1-3 are critical before fully departing to the field and in supporting and making sense of what comes back. In service education, student learning needs to serve the world before the world serves their learning. We have tried many variations on this structure and we’re happy to share learnings from our experiments.

For students, the skills learned from jumping in to an active system are the same skills that the future of work requires them to develop among others: agility, experimentation, effective communication, and creative problem-solving.

Further, it provides first-hand human experiences, not soon forgotten, that help students witness the positive and negative impact their technological tools can make.

* * *

What has been seen cannot be unseen

“What has been seen cannot be unseen”, writes C.A. Woolf : being exposed first-hand to human systems and the messiness of intervening to improve them will follow the students through their future experiences.

And if the business world does not evolve towards systems-thinking as rapidly as we, or our students, would hope, equipping more people to understand human systems will only hasten the much-needed evolution.

At the very least, these young professionals will be able to read a situation in terms of systems, both for themselves and for others, even if the dominant culture around them does not (yet). And at the best, they may, in their future leadership roles, take our societies to just where they need to be.

Kristian Simsarian, Ph.D. is an award-winning innovator, advisor, designer, and professor living in San Francisco. He was a design and business lead at IDEO for 18 years. He founded the BFA and Masters of Interaction design at California College of the arts in San Francisco. Through his company, Collective Creativity, he is helping leaders design innovative 21st century organizations for the greater good.

Charlotte Hochman is the Executive Director of Wow!Labs, accelerating innovation for companies, cities and universities in emergent situations. She has founded incubators and designed curriculums for leading institutions. Charlotte is a Fulbright scholar, an Entrepreneur-in-Residence at INSEAD, Designer-in-Residence at CCA in San Francisco, a BMW Foundation Responsible Leader, and a panelist at Obama’s Presidential Summit. Discover her work and access her guide "People spaces: How to create, convene and take part meaningfully in new spaces online”.

0 Comments